You probably are already aware that remote learning/distance education has been around for a few centuries — typically through mail service — so it’s not a new way to earn a degree.

[Tweet “There are noticeable yearly trends in attitude towards online degrees”]

What is relatively new is the online form of remote learning, in which content is delivered mostly via the Internet, in various formats including digital documents and videos (live stream or recorded). This allows students to study from practically anywhere, given an Internet connection and a computer/laptop or a suitable tablet.

The question is, are online college degrees as well-accepted as traditionally-acquired degrees, obtained through face-to-face instruction and tests? The short answer is, they have not be been as well-accepted, although that appears to be changing, yet there is still a ways to go before they are are accepted equally.

Overview: Online Courses and Degrees

A de facto definition of “online course” is one in which at least 80% of the content is delivered in some online form, with a maximum of 20% face-to-face requirement — either for orientation, exams or other reasons. By that standard, an online degree should consist of all online courses. If one or more courses for a degree program do not satisfy this “online course” definition, such degrees are referred to as “blended/hybrid learning.” (According to the 2014 Sloan Consortium /Babson Survey report, blended/hybrid instruction has 30-79% of the course content delivered online, whereas face-to-face instruction offers 0-29% of content online.)

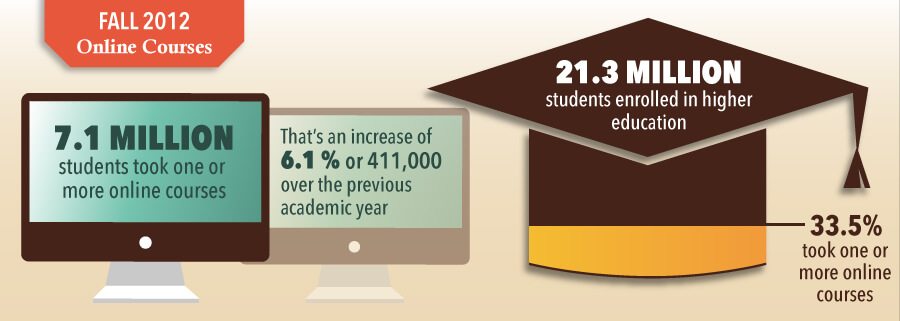

Online learning is a new enough form of distance education, in fact, that the U.S. Dept of Education only started requiring from institutions of higher learning their student enrollment figures for online degrees as of Fall 2012. Data for students taking one or more online courses for a degree program has been collected for a number of years – although not always accurately (duplication of student counts), and sometimes not distinguished from distance education courses by snail mail. Now, schools also have to submit enrollment figures for “online degrees.” So data for the former is much more readily available; data for online degree enrollment less so. Still, there are noticeable yearly trends in attitude towards online degrees and online courses in general, from several viewpoints, including students and employers.

Student Viewpoint

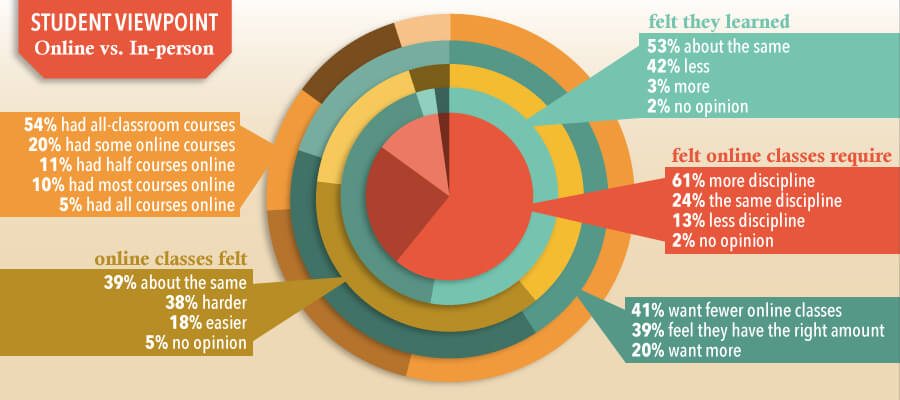

How do students feel about online courses and degrees? Casual browsing in online forums for discussions dating back to 2008 shows some students claiming that online learning is not for them, that they feel they do not have the discipline. The general feeling early on seemed that online degrees are for people who are autodidactic — capable of teaching themselves a topic of study without the benefit of a teacher. (History has a list of famous autodidacts, including Leonardo da Vinci and numerous famous inventors, writers, poets, photographers, architects, filmmakers, entrepreneurs, billionaires, politicians and others.)

That attitude is still present today amongst some students. A 2013 survey by Public Agenda of 215 community college students suggests they are still getting accustomed to online courses. It should be noted that this survey is of a very small sample size and thus does not necessarily reflect the entire student body in U.S. higher education institutes. Still, it is indicative of the division of attitude.

Regardless of how students feel, the number of students taking one or more courses online has been growing steadily — whether because they have to register or chose to register. The aforementioned Babson /Sloan Consortium higher education survey of online learning is conducted yearly (since 2003, for Fall 2002 onwards). The Jan 2014 report (conducted 2013, regarding 2012 enrollment data) sent questions to the over 4,700 (4,726) accredited institutions of higher learning in the United States, with over 2,800 (2,831) such schools responding — or a nearly 60% (59.9%) response rate. (According to the publication, institutions not responding “are predominantly those with the smallest enrollments, the institutions included in the analysis represent 81.0 percent of higher education enrollments.”) Here is some data from the Jan 2014 report, which was conducted in 2013 about the 2012 academic year (AY) online course/ degree enrollment.

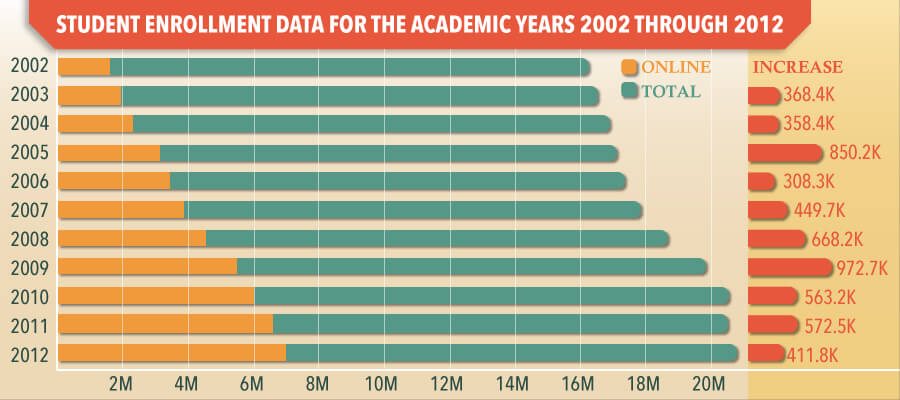

Here is student enrollment data for the academic years 2002 through 2012. Note that the # of students is in millions (M) except for the Increase column (Thousands – K)

So the peak increase in this time period was in Fall 2009 with almost a million new students (over the Fall 2008 count) enrolled in one or more online courses. However, the total number of students enrolled in 1+ online courses has been climbing from Fall 2002 through Fall 2012.

Opinions of Academic Officers

In the Babson Survey report published Jan 2014, over 2800 academic leaders (CAOs = Chief Academic Officers) responded. Most schools not responding are relatively small in size in terms of student enrollment. The 2010 Babson report claimed that non-respondents represented less than 20% of student enrollment in accredited institutions of higher education in the United States. (The 2014 report had nearly 300 more responding institutions than for 2010, thus the most recent survey’s respondents represent well over 80% of higher education students in the U.S.)

The survey of CAOs shows some interesting viewpoints. Firstly, there was a drop in 2013 in the percentage of CAOs who feel that “the learning outcomes in online education [are] the same or superior to face-to-face on-campus education. The percentage was 57.2 in 2003, peaking at 77.0% in 2012, then dropping to 74.1% in 2013. As well, the percentage of CAOs who feel that “online learning is critical to their [school’s] long-term strategy” dropped down to 65.9% in 2013, from 69.1% in 2012. In both cases, not-so-positive CAOs represented institutions with no online course/degree offerings. In contrast, around 90% of CAOs feel that it’s “Likely” or “Very Likely” that a “majority of all higher education students” will take one or more online courses within the next five years.

Despite that positive viewpoint from CAOs, schools have a ways to go in offering some forms of online learning, such as MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses). MOOCs — just one type of online learning format — are offered at only 5% of institutions, with only an additional 9.3% planning MOOCs. Some MOOCs have been immensely popular — U of Virginia’s Darden business school had 90,000 students from nearly 200 countries register for a business MOOC. However, less than 25% of CAOs feel that MOOCs are a sustainable way to offer online courses. So CAOs see the proverbial writing on the (digital) wall, yet some need more convincing about the optimal way to teach students online. This is important because some of the larger traditional universities are the ones typically offering MOOCs, and there is the potential for such schools to eclipse the online offerings of smaller or lesser-known schools.

What Schools Offer for Online Education

The opinions of a CAO towards an online degree appear to be independent of whether or not their school actually offers online courses and degrees. One estimate is that one or more online degree programs are already offered at over half of four-year colleges/universities in the U.S., including at the master’s and doctoral levels. (Some traditional schools only offer online degrees at the graduate level, with undergraduate degrees requiring on-campus instruction.)

In addition, a 2011 PewResearch survey of over 1,000 (1,055) college presidents (from two- and four-year colleges and universities of all types – private, public, and for-profit) indicated that over 3/4 (77%) of schools were offering online courses — 89% of four-year public colleges and universities, and 60% of four-year private schools. So the actual percentage of schools offering online courses is higher than 77% today. (Important to note: at that point, 51% of college presidents already believed that an online course was of equal value to an in-person course, while only 29% of the 2,142 members of the general public surveyed separately, also by PewResearch in 2011, felt the same way.)

Schools not yet offering online degrees but offering some form online course or at least online content have a few options. One is the aforementioned MOOC, typically open to both students and the general public, usually through a third-party provider. In the case of Coursera.org, who are partnered with 16 top universities, MOOC participants can take courses for free but are offered a “verified certificate of completion” for $49 per course — of which a slice goes to the institution whose material is being used. Predating MOOCs, schools have been offering publicly available, free course materials via Apple iTunes, or through some other online form of publication of course material (video, text, etc.). At the far end of the online-learning spectrum, some schools offer online content only to registered in-person students.

For some schools, online degree enrollment in certain programs is higher than for the on-campus version. For example, Indiana University’s Kelley School of Business launched their Kelley Direct online MBA program in 1999, and for the 2013-14 academic year, there were over 1,000 (1,072) students enrolled. This is more than for the school’s two-year on-campus program. The cost for Kelley Direct is also lower: $61,200 total for the two years, compared $93K for the on-campus program — a roughly 34% (34.2%) savings. That’s just tuition and fees. There are of course additional savings from reduced commuting and generally not having to be on campus. (Caveat: some schools charge extra for out-of-state students, even for online programs.)

There’s a similar story for University of North Carolina’s (UNC) Kenan-Flagler Business School with over 500 (551) online MBA students — also more than for their full-time on-campus MBA program. The cost is $96,775 (online) compared to $111,092 (full-time), or a savings of 12.88% for tuition and fees.

These are the only two online MBAs of the top 20 schools listed in Bloomberg Businessweek’s B-School rankings list. There are roughly 420 accredited MBA programs in the United States — most of which are in danger of having competition from online MBA programs. In fact, according to Richard Lyons, dean of Haas School of Business (UC Berkeley), some of these B-Schools could be out of business in the future — as much as half in 5-10 years. The implication is that they need to start offering online degree programs, and even then they will likely be competing with programs from the top business schools.

While some B-Schools outside of the Businessweek top 20 are offering online programs, not all are. There are a number of problems with which schools need to deal. One appears to be reduced interest in MBAs — possibly due to costs and the economy. For example, there has been a drop in GMAT (Graduate Management Admission Test) applications – a requirement of most MBA programs, merely to be considered a potential master’s student. Only 117,000 Americans took the GMAT as of the year ending Jun 30, 2012, which is a 6% drop since 2002. Nearly half (46%) of all U.S. full-time MBA programs had a drop in applications for 2013.

Some B-Schools already have fewer full-time MBA students than for part-time and executive MBA programs, collectively. As students in the latter two groups typically receive less financial aid than full-time students, there is more incentive for future students to go for quality online programs instead — and not necessarily to study business. Such schools are possibly in danger if they do not offer online degree programs.

Educator Opinions

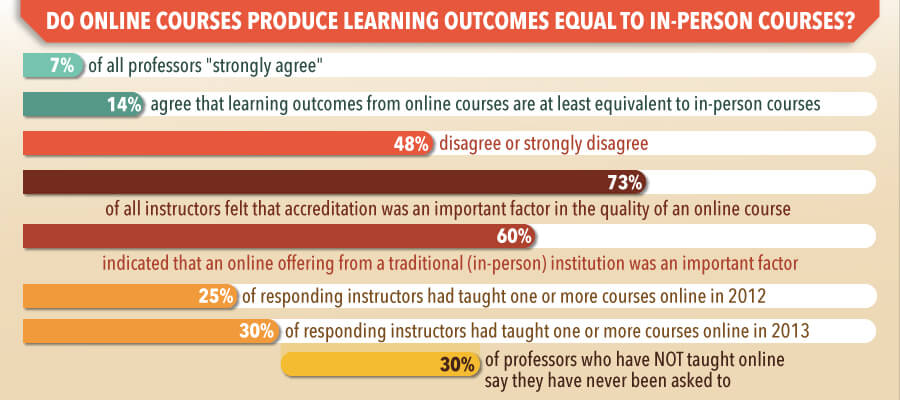

How do professors feel about online education? Inside Higher Ed surveyed over 2,200 (2,251 of 21,277 invited) from a variety of higher education institutions. The report was published in Aug 2013, and the overall viewpoint is that that those faculty members who had taught at least one online course were more positive in general than those who had not taught an online course. This includes attitudes about the quality of online learning, about the outcome for students, and overall effectiveness compared to in-person courses. Professors were more skeptical when talking about online courses in their own departments and courses as opposed to about online education in general. Tenured faculty members were less likely to agree (only 17% of this group) about the learning outcome of online courses compared non-tenured faculty (~25% of this group).

Here are a few of the lengthy list of statistics, below, that were collected in the survey. Please see the Inside Higher Ed survey overview for more statistics, as well as a link to the full report.

Employer Concerns

As with students, CAOs and faculty, employers have a mixed bag of opinions about online degree credibility when it comes to job candidates. Various surveys suggest that employers evaluate job candidates on a case-by-case basis when it comes to online degrees.

The aforementioned 2013 Public Agenda report also surveyed 656 human resources staff at employers seeking job applicants with a post-secondary degree. The survey found that 80% of employers admit there is a need for online education, with older students being a key consumer — only 50% felt the same way for first-time college students recently out of high school. Yet, 56% still “prefer a job applicant with a traditional degree from an average school over an applicant with an online degree from a top university, compared to 17% who prefer an online degree candidate.” This may be due in part to 42% of employers surveyed thinking that students learn less from an online-only program, although 49% feel students learn about the same, 4% feel they learn more, and 5% don’t know). Nearly 3/4 (about 74%) of employers felt that it takes the same amount (29%) of discipline or more (45%) for online learning over in-person learning; 23% felt the opposite, that online-only degrees take less discipline. A similar question posed asked whether online-only degree programs were easier or harder to pass, with 39% saying easier, 13% harder, 41% about the same and 7% don’t know.

[Tweet “80% of employers admit there is a need for online education”]

Some of this Public Agenda data might seem like bad news for online learning, although other studies found slightly more positive viewpoints, at least for some aspects regarding online degrees. Time Magazine wrote, in late 2012, that employer views on online degrees had slowly improved in the preceding 5-10 years, according to SHRM (Society for Human Resource Management). An Aug 2010 SHRM survey found that over half of HR managers stated that two candidates of equal experience would not be evaluated differently if one had an online degree. Nearly 80% (79%) indicated that they had hired someone with a degree from an online program in the previous year. Despite this, 66% still indicated that applicants with online degrees were not viewed as favorably as an applicant with a degree from a traditional face-to-face learning program. Ultimately, an HR person’s familiarity with a particular program and online education in general will play a significant role in their perception of an online degree, since it’s part of their nature to be conservative about candidates.

US News and World Report, between late 2013 and early 2014, found a slightly more positive shift in opinions about online education from employers/HR managers. In general, some recruiting companies indicate that clients (employers) are asking less often about online degree program quality, especially if they’re satisfied with other factors in a job candidate. More specifically, one recruiting services firm for over 100,000 SMBs (Small and Medium Businesses) found that 75% of clients (i.e., employers) had no issues with candidates having online degrees , while the remaining 25% would likely stand firm on not hiring such candidates. Still, it’s important to the 75% that online degrees be accredited.

So the gist appears to be that employers are starting to at least appreciate some of the positives of an online degree while still trying to understand other aspects. The more online education comes up in national discussion, the more all parties involved will gain a better understand of its pros and cons. Unfortunately, in the recent past, discussion of online degrees had to do with “diploma mills,” which were either unaccredited institutions, or those “accredited” by fake accreditation organizations.

[Tweet “In the recent past, talk of online degrees had to do with “diploma mills”]

It will take some time to shake off that stigma, although some employers have already done that. So what are employers looking for in a job candidate? Primarily, someone who is qualified for the job, preferably properly trained. Since most college grads do not come out of college trained in their chosen field — unless they were in a work program during college — at the least, employers want candidates who are properly educated and thus have the basic knowledge required to perform the job in question. That is partly why older students with work experience and an online degree are currently likely to be viewed more favorably than someone younger with the same online degree.

When it comes to degrees from traditional universities, employers often care more about whether the degree is from an accredited program than what college. Obviously, not everyone can go to a “top” college or university, for various reasons (limited enrollment, qualifications, budget, geographic location). Employers typically evaluate job candidates in several facets, including the specific degree, the school, and the candidate’s skills and qualifications. There are similar but additional criteria for a candidate with an online degree:

- Candidate qualifications and experience, regardless of degree source and delivery format (online or in-person).

- School brand value — An online degree from a respected traditional (brick-and-mortar) school usually ranks higher, possibly above any degree from a lesser known school, but not for all employers.

- Accreditation — If the school is traditional although not as well known, having legitimate local accreditation for online degree programs is important. The same goes for an online-only school, where all their degree programs are offered online.

- Type of school — a non-profit school is likely to be perceived more favorably, although not always.

Overall, some employers actually favor online learning for their employees, and occasionally provide partial or full tuition reimbursement. An online degree program for existing employees enables the latter to continue working — something a traditional degree program might not offer. As the number of students taking online degrees increases, as well as the increase in the number of schools offering such programs, employers may adapt to accepting such credentials on par with traditional degrees — whether in regards to new or existing employees. As for any disruptive technology, majority acceptance takes time, although there appears to be a shifting towards acceptance of online-only degree programs.

References

Information for this article was collected from the following Web pages and sites.

- http://www.businessweek.com/articles/2014-03-14/online-programs-could-erase-half-of-u-dot-s-dot-business-schools-by-2020

- http://www.pearsoned.com/babson-study-over-7-1-million-higher-ed-students-learning-online/

- http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2011/08/28/the-digital-revolution-and-higher-education/

- http://www.publicagenda.org/files/NotYetSold_PublicAgenda_2013.pdf

- http://sloanconsortium.org/publications/survey/grade-change-2013

- http://nation.time.com/2012/10/18/can-an-online-degree-really-help-you-get-a-job/

- http://www.usnews.com/education/online-education/articles/2014/02/28/what-employers-really-think-about-your-online-bachelors-degree